Bottle meditation

Late night musings on lead service lines and why we need both water utilities and water filters

It’s pitch black, but I can feel the tug of my son’s lips on the bottle and hear his snuffling so I know he’s eating. I’m sitting in bed, it’s 10 pm, my six-month-old in my arms. I’ve not posted in a while (nor done much of anything else), and this is why. This little lump in my arms, who is constantly hungry it seems. In fact, infants need 2-3 times as many daily calories for their body weight than adults do. So, yes, constantly hungry.

The same goes for fluid intake. Babies need about 100 milliliters of fluids per kilogram of body weight per day. The average adult needs only about 35-40 milliliters per kilogram per day. If I drank as much as my son does for the size of his body, I would need about 7 liters of water a day. (I feel good about myself if I finish a single Nalgene.)

While he drains his bottle in the dark, I think of the water it was made with. The water that, up until just nine days before he was born, was flowing through a lead pipe into our home. A matter of days after I wrote this post about why you might want to filter your water at home, I found a Brita pitcher on my porch and a letter from the city water department saying they had identified a lead service line leading to my house.

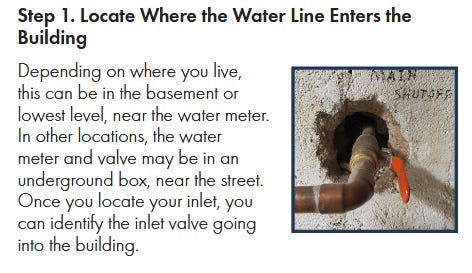

I was appalled. I mean, I study this stuff. The first thing I did when we bought our house was check the water line. I could see with my own eyes a shiny copper line leading into the house at the shutoff, and could also see the copper coming from the street in the meter pit in the front yard. Given the research about how obviously bad partial service line replacements are for lead leaching, I figured nobody would have done that! I even used pictures from my own house to help write the guidance for RTI International’s Clean Water for U.S. Kids program (where I was working at the time) on how to check for a lead service line in your home. Check the color, scratch the surface, use a magnet, etc. But turns out, these little rules of thumb won’t cut it, especially in older homes (mine was built in 1911). Individual homeowners can check what comes into the house, but they can’t dig potholes in the street to check the utility-owned side of the line for a partial replacement or lead gooseneck (the curved part of the pipe that ties into the water main).

I can’t think of a better example of the need for both the essential services of water utilities and the household water filter industry, or what I have called the “formal” and “informal” water sectors. For over 100 years my house was sitting there with a lead line, and, until recently, regulations didn’t require the utility to do anything about it. In that gap, I hope previous homeowners were filtering their water, and wow am I glad I did so when my first son was born three years ago. Despite my confidence that I didn’t have a lead service line, I still followed my own advice and installed a filter out of precaution. There are just too many unknowns out there. One of them being, it turns out, the few feet of pure lead connected to the water main under the street.

So I’m glad for the additional treatment barrier I could elect to install under my sink, and for the industry that undergirds the manufacture and consumer safety testing of such products. At the same time, I’m also grateful for the city’s efforts to remove those few feet of lead line, despite also having a filter. I can go to Lowes and pick up a filter cartridge; I can’t start digging up my street with a backhoe or drill 50 feet horizontally underneath my house and yard, like these guys:

This is why we need both — the large-scale, costly institutional efforts to improve the quality of public water for whole communities and the individual consumer options to install last-mile barriers where regulations, funding, and central treatment fall short. Now, if only we could devise better ways for these two different but parallel sectors to intersect and collaborate. Where the filter industry could supplement and bolster the work of centralized treatment for compliance and consumer confidence, rather than erode public trust. Or where water filters could be provided through equitable mechanisms of service delivery, like the water flowing through the pipes, not just as a privilege for those who can afford it. The Brita pitcher that showed up on my porch is one example, but a temporary one; a stopgap used by utilities while disturbing the lines. There could be better ways as water filter technology and monitoring improves. More on that later, perhaps.

For now, I’ll leave you with this: a video of my son, Jamie, at 6 months—his brain at this stage a sponge to the neurotoxic effects of lead—taking his first sips of water.